Introduction to the Baradla Cave

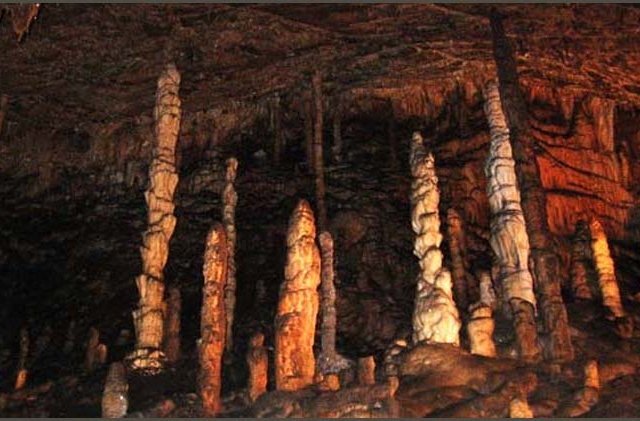

The karst’s emblematic Baradla cave stretches all the way across the border to Slovakia. The total length of the Baradla-Domica Cave System measures 25 km (15.5 miles), of which a 5.3 km (3.3 mile) long section is lying on the Slovakian side. Due to its length, activity and richness in cave formations. the Baradla Cave is undisputedly the most remarkable cave not only in Hungary, but also in this entire temperate zone. It was declared a natural monument as early as 1925, has been under protection since 1940, and under strict protection since 1982. Up until the last century, it held the status of the second longest cave in the world. Although its rating has decreased in the following decades, it still unquestionably remains among the top caves worldwide.

Exploration History

The first record of the Baradla Cave dates back to 1549 when it was mentioned in a work by G. Wernher printed in Basel, but without naming it and unfortunately incorrectly locating it. This data was cited by many others in the following 200 years, but Mátyás Bél was the first to call attention and correct this error in his geographical book entitled Notitia (Vienna,1742) but gave no additional description of the cave. In his manuscript written about Gömör County, he accused the local residents of negligence for not making any exploration of this monumental cave. We can find the first detailed documentation in the German language Ungarisches Magazin in 1781. The Hármas kis Tükör school book included a chapter on the cave in the Hungarian language in 1788. József Sartory and János Farkas provided the first survey and description in 1794. Although the original work has been lost, a copy of the map was found in 1962 and is thought to be the first detailed cave-map in the world carried out by an engineer. The first detailed description and printed map of the cave is thanks to Keresztely Raisz, an official land surveyor. His successor, Imre Vass was the first to succeed in getting through the so-called "Iron Gate," several year’s long draught resulting in unusual low water in the cave,thus making it passable. He discovered an additional 6 kilometres of the main branch, and made a detailed description and an artistic map of the cave and the surface. His works were published both in Hungarian and German in 1831. John Paget, the English traveller, reported in his book four years later that despite its worldwide importance, little had been done to protect the Baradla Cave or improve the facilities for visits in the cave.

A century later, Péter Kaffka discovered a new 500 m section in the main passage. In 1932, the most successful director of the cave, Hubert Kessler managed to reach the Domica Cave by passing through the "Siphons of the Styx," therefore justifying the long-standing theory that the two caves are connected. Since then, many other explorations have been dedicated in order to map and discover the Baradla Cave and provide new information about this underground world.

Cave Development and Construction Works

Early records about the cave advise visitors to hire a guide as one can be easily become in the labyrinth of narrow tunnels sometimes blocked by rocks. Although some construction works were carried out in the year of Palatine Joseph’s visit in 1806. The entrance and the major passages were widened with explosives, and numerous bridges and planks were laid over the streambed. However, no intention was ever shown to actually protect the cave during this time.

Writings from the 1860's report that the gardens of the village are often decorated with stalagmites from the cave, torches are spoiling the cave formations and the hired guides amuse visitors with shooting at the bats in the cave. Sophisticated construction works began only in 1881 when the Hungarian Carpathian Association took over the management of the cave, a new shelter house was built at the Aggtelek entrance – the first of its kind in Hungary. Thanks to Kálmán Munnich’s efforts, bridges and pavements were renovated, the entrance at Vörös-tó (Red Lake) was established enabling to start one-way tours from Aggtelek. He also prohibited to light with torches, a new passage was completed and named after its explorer Munnich. Károly Siegmeth's articles, books and lectures helped to popularise the cave, as did Károly Divald's photographs and resulting postcards in the 1890's. Annual visitors to the cave numbered only a couple hundred in the 1830's, but by the turn of the century this number exceeded 1000.

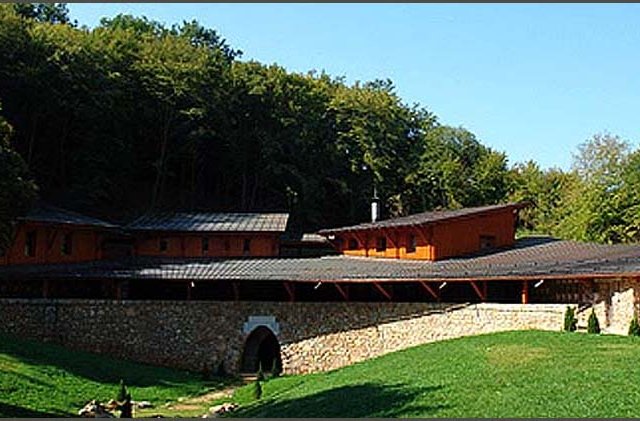

Once the cave was declared a national treasure in 1925, the government financed concrete pavements, bridges (some of them still in use today) and stone staircases. The Jósvafő exit, planned by Péter Kaffka, was completed in 1929. Kaffka also succeeded in reaching the endpoint of the Jósvafő. The highlight of the development work was in 1935 when lighting and electricity were installed in the cave for areas dedicated for tourists. The following years came to be viewed as the "Golden Era" in the history of the cave. Director Hubert Kessler erected several new buildings, including the Barlang Hostel in Aggtelek, Hotel Tengerszem in Jósvafő, a new concrete road leading from the village to the cave, and a tourist path around the Tengerszem Lake. These works helped improve tourism on the surface as well. After World War II, a signifigant amount of renovation was necessary. For example, the electrical system was modernised, the so-called "Concert Hall" and a new visitor centre at Aggtelek were established.

The Tourist Bureau of Borsod County managed the cave for several years, but in 1984 it was re-organised and placed in the hands of the Bükk National Park Directorate. A year later, the Aggtelek National Park Directorate was established. Reconstruction between 1991-1994 renovated the Aggtelek section. Between 2003-2005, the Jósvafő passage was modernised thanks to funding from the EU PHARE Programme and Hungarian government resources. Lighting is the focus this year. We will modernise the illumination in the caves with energy-efficient, environmentally-friendly LED bulbs which will also act to minimise the developingment of lamp-flora in the caves. The programme is supported by and will be realised within the framework of EU project KEOP- No.3.1.2/2F/09-2009-0015.

Archaeological Research and Finds

The high number of citations about the archaeological excavations carried out in the Baradla Cave emphasise the importance of this cave in archaeology. However, we must admit that earlier excavations have sometimes mixed and injured the different archaeological layers and deposits, making present day scientific research almost impossible. The first relevant excavations can be attributed to Jenő Nyáry, though following generations have complained about the negligence of these works as they failed to provide relevant, important information on the sites. Ottokár Kadić, Károly Siegmeth, Lajos Márton and László Vértes are among the most well-known archaeologists carrying out research here during the last century.

The remains prove that prehistoric man dwelled in the cave, and purposely built shelters to protect themselves from the moist and cold air of the cave. Regrettably traces of the stilts are almost invisible now. The majority of the remains are from the Neolithic Age, such as personal articles made out of bones and stones (similar to items found in other karst caves of the karst as well). People of the Bükk Culture lived here. Their pottery was made without a potter’s wheel, and the motifs of the thin-walled bowls are embellished with bone combs and painted in white, yellow or red mineral paints. These relics belong to the Alföld Linear Pottery Culture. Another exciting piece of evidence of cavemen is in the Hall of Bones, where 13 skeletons were buried in a squatting position with knees drawn under their bellies, face down, and each with a large stone placed on their backs. Researchers relate these findings to the Kyjatice Culture. Numerous everyday utensils, gold jewellery and weapons reveal the traces of our ancestors who used the cave either as a shelter, a burial site or as a cult site in the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age.

Formation of the Cave

The Baradla Cave was formed some 200-230 Million years ago in Triassic limestone when the territory was covered by a gradually deepening sea.

The oldest rock formation can be found in the Jósvafő section, the so-called dark-grey and black Gutenstein Limestone. It is heavily fragmented and contaminated, making it eminently suitable for forming passages but inappropriate for the precipitation of dripstones. Most parts of the main branch are formed from light-grey Steinalm Limestone that is perfectly proper for karstification and forming dripstones. Fossil-like remains of green alga, ammonites and sea-lilies can be observed in this rock. The branch from the Iron Gate to the Aggtelek exit were deposited from a relatively clear kind of stone - the Wetterstein Limestone that is also excellent for forming dripstones. After the Triasic Era, the area was elevated above sea level . During the formation of the hills, the solid blocks were strongls shattered.

The meandering main passage is a streambed averaging 10 metres in width and 7-8 metres high. Some sections widen into large rooms, while others narrow to be impenetrable.

As water seeps through the cracks on the surface, rock is dissolved by the natural acid content of rainwater. This dissolution process produces a distinctive landform known as karst. Cave formations (speleothems) like dripstone columns, stalactites, stalagmites, draperies and rashers were developed by the deposition of calcite from dripping water. Flowing waters created limestone rims and pools in the caves.

The cave catchment area extends approximately 40 km2 in area, and much remains to be discovered. Imre Vass first called attemtion to the possibility that there may be a system lying beneath the one wew currently know about. For example, according to water tracing experiments, a hypothetical underground cave system must exist under the main branch of the Baradla-Domica Cave System. Scientists conjecture that there are two existing cave sytems hydro-geologically independent from each other. Rainwater also infiltrates through the surface and reaches the underground world through sinkholes such as the Little Baradla, the Acheron, the Little and Big Ravaszlyuk Sinkholes.

Climatic Conditions of the Cave

The first measurements carried out by Imre Vass demonstrated the average temperature in the cave to be around 10 °C (50 °F). These measurements were later confirmed by the monitoring processes of the 1950’s. During winter, the 25-30 °C differences between surface and underground air temperatures can result in huge differences in atmospheric pressure causing a strong wind in the cave.

Relative humidity is approximately 95-100%, giving a sense of dampness. Carbon dioxide content of the air cannot be felt by sensory perception, but measurements assessed 0,1% carbon-dioxide in the main branch, while the maximum content in the cave exceeds 4%. The average radon activity of the cave is 2 kBq/m3, with the maximum value at 13 kBq/m3 in the Labyrinth.

Thanks to these unique circumstances, the Baradla Cave also has medical advantages for visitors suffering from respiratory organ diseases who can experience its positive health effects even after only a short tour.

Flora and Fauna in the Cave

Every type of cave-inhabiting animal can be found in the caves! One can find troglodytes (cave-limited species) and troglophiles (species that can live their entire lives in caves, but can also occur on the surface), trogloxenes (species that use the cave only for a period of their life) and animals that accidentally pop-up in the cave.

The first zoological information stems from the pens of Keresztély Raisz and Imre Vass, but the first true scientific observations can be attributed to János Salamon Petényi and Imre Frivalszky. As a result of their studies. The most unique species of the Baradla Cave were described, such as the whitish blind isopod (Mesoniscus graniger), Porrhomma rosenhaueri and Meta menardi (small spider species). Another important milestone in the zoological history of the Baradla was when in 1903, Tódor Kormos and Jenő Győrffy found the Austrian aprófutonc (Trechus austriacus, a kind of beetle) and the Hungarian blind ground beetle (Duvalius hungaricus), both carabid species. The number of identified species has risen to 500, including endemic species like flies (Dipteria), springtails (Collembola), Nemathelmintes, Annelida and Protozoa. Mention should also be made of the cave orb-weaving spider (Meta menardi) and the Aggtelek blind amphipod (Niphargus aggtelekienis).

Despite the mycological and bacteriological research that have registered a number of species, first carried out by Endre Dudich, the air of the cave is regarded as almost sterile.

The increasing number of tourists reshaped, or rearranged the compound of bat colonies in the cave as bat species tolerating disturbance replaced other less tolerant species. Nearly 20 bat species have been identified here; among them the three Rhinolophus species (particularly the Rhinophus euryale) and the Mediterranean horseshoe bats are of outstanding importance.