The Földvári Aladár Cave

.jpg)

Along the left bank of the Bodva River, nestled within the northeast ridge of the Szalonna Hills, one finds the once 384 m high Esztramos Hill. “Once,” because from 1948-1996 stone quarrying decapitated the summit, whose remarkable and emblematic shape now only reaches 312m above sea level. The so-called “Rákó Summit,” a lonely stone-island compared to the original summit, remarkably preserves a number of species of high botanical value. Moreover, it conceals valuable underground chambers rich in speleothems (cave formations and mineral deposits).

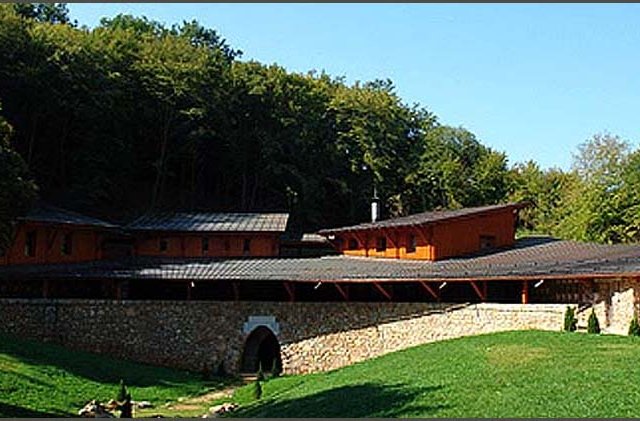

These caves, extending on two distinct levels at the altitude of 320m and 305m, became strictly protected in 1961. Among them, the Földvári Aladár Cave, named after an esteemed Miskolc University geology professor, was the first to come under state protection on the territory of an operating mine. The first tangible result was that the mine was legally required to bypass the caverns and preserve the area fully intact.

Discovery and Exploration

This cave was discovered as a result of one of the mine-related explosions carried out in October, 1964. The natural entrance was not discerned until a later date. The approximately 190 m long chamber system is composed of three spacious rooms that were discovered by a speleologist group called Vörös Meteor (Red Meteor). The first published mention (Dénes, 1964) and the first map (1967) can also be attributed to their efforts and surveys. Years of adversity and unclarified legal status followed the discovery. Some questioned if its protection was in the interest of the national economy. A final decision was made in 1967, and a 50m x 150m protective barrier was erected around the caves. The cave’s historic preservation was in no small part thanks to the arm-twisting support of the speleological profession. By then, however, the cave had already suffered irreversible damage through theft and vandalism. Many of the most interesting and valuable dripstones and formations had been stolen or smashed. Unfortunately, no photographic evidence exists that can tell us more about the cave’s earlier, intact condition. All we can do is imagine how exuberant it would have been when the first explorers caught sight of this untouched, pristine wonderland. Even so, what remains is still stunning and abundant enough to warrant its inclusion in the Aggtelek karst and National Park.

The Natural Environment

A closed entrance was built into the side of the south-eastern protective wall. Beyond the entrance one finds internationally important paleontological finds, monuments to the site’s industrial past and filled karst fissures. Although it can only be observed on the ceiling

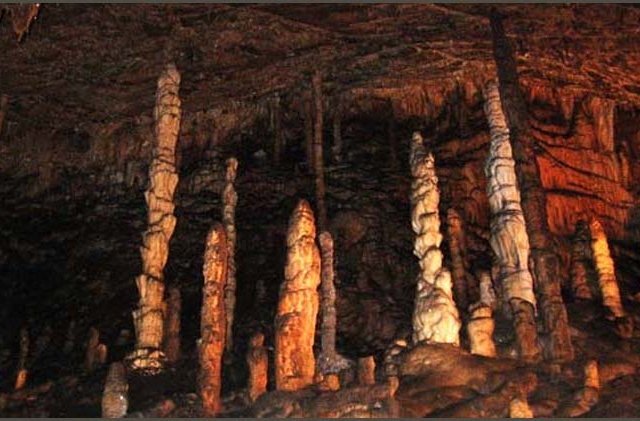

since most of the cave is abundantly covered with dripstones, the surrounding rock is light-grey Steinalm Limestone from the Middle Triassic Age. Strong tectonic activity resulted in 10 m wide and 20-30 m long halls and smaller side chambers. Stalactite and stalagmite formations follow fracture lines in the rock mass. These elements reveal in different ways how the cavities at water level were formed. The ceiling plane most likely just marks the former water level in the system. Paleontological excavations have established that the Földvári Aladár Cave is, at approximately 2 million years old (the Upper Pliocene at the latest), is provably among the oldest known caves in Hungary.

Formations

Over time, the gradually increasing water levels within the system guaranteed abundant time to decorate the spacious cave rooms with an abundant mass of interesting mineral precipitates. Stalactite draperies, as well as large and small basins cover the streambed and the walls of the cave. Some pools are full of water, while others are empty, with only their slightly elevated rims providing evidence of earlier water. The most striking treasures in the Földvári Aladár Cave are to be found in a band about 306-307 m above sea level. This is an unusual occurrence among caves 305-320 m above sea level, and a unique opportunity for study.

Over time, the gradually increasing water levels within the system guaranteed abundant time to decorate the spacious cave rooms with an abundant mass of interesting mineral precipitates. Stalactite draperies, as well as large and small basins cover the streambed and the walls of the cave. Some pools are full of water, while others are empty, with only their slightly elevated rims providing evidence of earlier water. The most striking treasures in the Földvári Aladár Cave are to be found in a band about 306-307 m above sea level. This is an unusual occurrence among caves 305-320 m above sea level, and a unique opportunity for study.

The cave’s other outstanding speleothermic feature, its stone chandeliers, unfortunately could not be saved by the protective wall. Continued explosions and vibrations from nearby mining operations caused their eventual destruction. These unusual manifestations hung suspended from the cavern ceiling by only a thin “neck” of stone, of which now there is little evidence. Therefore, much of the cave debris consists of sedimentary fill and the remains of fallen and vandalized stone chandeliers and other stalactites. Debris in the entrance hall is made up of fallen blocks, and washed down red clay whose pigments have acted to color some of the diverse shapes. Only small, 15-30 cm specimens remain on the cornice around the ceiling where once and thousands of stalactites held firm.

The best preserved formations, such as “blades,” and “wreathes,” are located at the innermost end of the ceiling along fractures. Elsewhere, bizarre worm- and antler-shaped heliktites decorate the walls, “cave popcorn” expanding like mushroom fields, and small, coral-like shapes are typical.

The most unique gift of the cave, from a professional point of view, is unquestionably the “moon milk” covering the dripstones in several centimetres thick dull-white, soft material in the middle hall. This example of moon milk, unique in Hungary, is actually composed of calcite, or more exactly, of its variant called lublinit. It is different to manifestations found in the Buda or Villány Hills which are made up of magnesium carbonate minerals. The specific height of the moon milk indicates that its development was the result of precipitated standing water, much like the older formations of pointy little calcite crystals.

On the basis of various indicators concerning the formative conditions, the bulk of the caves and speleothems were created during a very early geologic period. This leads us to the conclusion that the fractured surface and “scarring” is actually a re-crystallized structure.

Nowadays, dripping water can only intermittently be detected, and the active development of “living” formations represents only a fraction of the formations in the cave.

All in all, strict protection of the Földvári Aladár Cave is justified on the grounds of even just the surviving unique speleothems.

(ANPI archive, Csaba Egri)